Brideshead Revisited, Revisited

Memories, class struggle, and young love at Oxford. What a movie unlocked for me.

“I wanted to make something sexy. I wanted to make something about boys,” - Emerald Fennell, writer/director, Saltburn.

In the autumn that I “went up” to Oxford, long ago in 1981, Brideshead Revisited began airing on British television. I knew the novel. A high-school friend had given me a copy the previous summer, and to this super-Catholic scholarship boy with an entirely sublimated longing for other boys, it was, as you might imagine, something of a revelation.

At a point in my childhood I no longer recall, I had deduced that Oxford was special. It was, I surmised, the most plausible gateway to the world that would otherwise be denied me, and I aimed for it with near-pathological dedication. With no dating or sex life in my teens, and no driving license, I mastered instead the intricacies of Cicero’s Latin style and revisionist arguments about the English Civil War, and won the top scholarship in history at Magdalen College at the tender age of 17.

And within days of settling in, I became aware of the social circles around me that had long been forged in the private schools of the British upper classes. A big part of me despised their easy privilege, their plummy vowels, their Barbour jackets and embossed invitations, their Pimms and pasta-and-pinot dinner parties, and their disparagement of anyone who was seen to be trying too hard (which, of course, was me). Another part of me was enthralled, beguiled, entertained. And by virtue of my gregariousness and curiosity, I began to drift into their milieu, even as I chafed against it.

And I fell in love with one of them. It was a blinding infatuation shadowed from the start by the fear that it wasn’t reciprocated, or might be lost. There was no sex; the closest we ever got physically was when he helped me tie a bow-tie from behind in a mirror. We would talk and talk endlessly about everything, late into the night, both of us very Catholic, perversely non-leftist, and at the age when your intelligence peaks. In the vacations, we wrote each other long, handwritten letters by ink pen. When he eventually dropped me — suddenly, without warning, in front of others — I couldn’t function for a while. I sobbed bitterly, day after day, until my roommate was forced to ask: were you in love with him? Are you gay? And I kept sobbing. It was a classic moment of homosexual rejection; but also a love affair that had never mentioned its name, never articulated itself, never actually been real, even though it had overwhelmed me.

All of which is to say that the new movie Saltburn — by Emerald Fennell — was almost written, you might say, to yank my chain. It is centered on the story of one Oliver Quick, an awkward, middle-class scholarship boy, who goes up to Oxford and falls for a winsome aristocratic charmer, and is swept up into a world of country houses, bohemian toffs, strange rituals, and endless money. (Some minor spoilers ahead.)

Although most of the reviews scant this aspect of the film, it is, at its core, an unconsummated first love story. Oliver, for all his pride, falls for Felix, for Oxford, and for the British aristocracy. Felix, in turn, doesn’t quite fall for Oliver, and then, after a revelation about Oliver’s past, cuts him off entirely. One scene devastates: Oliver has a bathroom that is shared with Felix. One day, without warning, Oliver finds the door to it locked. And this simple lack of reciprocation is what fuels everything else that happens in the film. I have to say that in an epic scene, when Oliver is lying on top of Felix’s newly-dug grave, his convulsive sobs, his despair at the loss, took me right back to the trauma of the summer of 1983.

The film is also hilarious. The wastrels, eccentrics, and buffoons of the family Oliver goes to stay with are brilliantly drawn. Richard Grant is fantastic as a blithering Lord of the Manor; Rosamund Pike as the elegant matriarch had me cackling with joy; and in a cameo as a house guest who had outlasted her welcome, Carey Mulligan gives us something between an episode of Absolutely Fabulous and a Tim Burton flick. She flinches ever-so-slightly as the family drops her, but her eyes become black holes of hurt. She subsequently kills herself (or was it murder?), prompting the fabulous line from Pike: “She’d do anything for attention.”

And to my surprise, the portrayal of this entire class is shockingly close to everything I remember about them all those years ago — the strained accents, the casual cruelty, the tart phrases, the cloying bohemianism, all going nowhere stylishly. It’s no surprise: Emerald Fennell is one of them, educated at Marlborough and Oxford, with stonkingly wealthy parents, and she did the whole Brideshead thing at Oxford with gusto, a good quarter-century after my class did. You can absolutely imagine the family in the movie calling their daughter something that sounds like a lurid vegetable. So the portrait is not just blindingly accurate; it’s also forgiving. From a profile of the filmmaker:

[Fennell] describes herself as “absolutely the person [at her college] with a Brideshead fetish” because like “a basic bitch” she fully embraced the romantic Oxford fantasy. “I would be wearing a pair of men’s 1930s trousers and braces,” she says with a laugh. “So much of this film, and so much of everything I make, is me trying to come to terms with what an embarrassing person I am [and] what embarrassing people we all are.”

It’s interesting to look back at my own somewhat embarrassing escapades at Oxford and realize I too was just being a “basic Brideshead bitch.” And why not?

There is not a trace of tedious wokery in Saltburn, no brutal lefty takedown of the upper classes, no damning exposure of privilege, nothing really about race, thank God, (the biracial American cousin is the least interesting of all the characters), or gender, for that matter. If anything, you become increasingly fond of these rich, daft fools, with their fancy dress parties and faux hospitality, and bulimia, and sexual compulsion.

And the plot slowly exposes what is, in fact, their deep vulnerability in the face of a very smart, Mr Ripley-style, sexy-as-fuck interloper. In one scene, Felix and friends are lounging nude in a meadow, reading. Oliver arrives, surprised and instantly uncomfortable. They demand he join them. As his pants come down and his prodigious, un-mutilated member reveals itself, he is suddenly their master. They all but bow (which made this scholarship boy cheer).

Is Oliver gay? Nah. No gay man could go down on a menstruating vagina with the aplomb that Oliver does (in one of several scenes when I had to put my hands over my eyes). Is he straight? I wouldn’t be so sure of that either. It’s hard to imagine a straight man observing a friend jerk off in a bath tub; and after his friend has left, felching a mix of water and jizz from the plughole. Is he motivated by greed, revenge, or longing? No clue. The enigma of Oliver is created by Barry Keoghan, the slow-boy character from The Banshees of Inisherin (another film I loved). It’s another virtuoso performance — hideously under-stated until the end, but always believable, from the initial, bad haircut to the cold, sadistic glee of the ending.

You feel for him at first as he seems lost in the bewildering world of Oxford; and you cheer for him, even as doubts emerge; but you never truly know him. A whole bunch of critics have assailed the movie as shallow or empty. But it is no more shallow and empty than Oliver. And by the end of the film, you want him too. How Keoghan manages to pull off all this enigmatic evil is beyond me; the performance is up there with Dustin Hoffman’s in The Graduate — except it is Oliver who seduces the matriarch this time. And she had no idea what was coming.

The resilience of all this frippery — the still shocking hold the English aristocracy has over the global imagination — proves the British class system we young Thatcherites were intent on blowing up had a few tricks up its sleeves yet. And maybe seeking its oblivion was short-sighted (as Oliver clearly came to believe). Orwell famously wanted to abolish all of it, but the history of the British elite has its glories as well as iniquities; its culture has been woven into the very concept of Englishness; and for a couple of centuries, it created the entire modern world we live in. The lovely aspect of the film is that it neither condemns nor defends this class; it seeks to understand and appreciate them. Their foe is an anti-hero. They are not just symbols of oppression; they are people too, with all the wounds that flesh is heir to.

I remember, in that respect, one Oxford moment when I was mouthing off in front of my unreciprocated love about some idiotic upper-class twits who had no business being there. “That’s a little harsh. We’re people too,” he countered, or something like that, as my memory serves. “Hating all of us means hating me; but I didn’t choose who I was at birth; it was my fate, not my choice, just like yours.” I was caught short. In him, the Catholic imperative won out over the class struggle. There was also decency in this elite, I surmised. There still is.

Oxford as the romantic symbol endures, of course. Its beauty imprints on you. In a couple of the scenes (like the one pictured above), I could actually see the windows of my old rooms in Magdalen’s New Buildings — built in 1733. For a middle-class boy who was the first in his family to go to college, it was, inevitably, a dream I kept expecting to wake up from. To live in that Palladian elegance, to walk to lectures through a medieval cloister, to attend evensong and hear Palestrina and Tallis over and over again, to study where C.S. Lewis taught and Oscar Wilde invented himself: well, I never recovered. It was such an intense love I felt the need to run away from it for half a lifetime, in case it entrapped me for good. It remains as intoxicating as a first love; and still causes me acute pain to remember its evanescent joy.

(Note to readers: I’m on Real Time with Bill Maher tonight, and that’s why the Dish is a bit later than usual this week. If you’re already a subscriber, click here to read the full version of this week’s issue. It also includes: a fantastic but depressing talk with Jeff Greenfield about Trump and political history; a ton of reader dissents over the war in Gaza; eight notable quotes for the week in news; 26 pieces on Substack we recommend on a wide variety of topics; an MHB of a PSB karaoke cameo; a wonderful wintry view of Bend; and, as is tradition, the results of the View From Your Window contest — with a new challenge. Subscribe for the full Dish experience!)

From a new subscriber:

I’ve followed you for many years, since the days of The Daily Dish. Thanks for the discounted price over the holidays! It convinced this senior with limited fixed income to finally get a paid subscription. And while I subscribe to other free substacks, The Weekly Dish will be the only one I pay for!

New On The Dishcast: Jeff Greenfield

Jeff is a TV journalist and author focused on politics, media, and culture. He’s been a senior political correspondent for CBS, a senior analyst for CNN, and a political and media analyst for ABC News. He has authored or co-authored 13 books, including If Kennedy Lived, When Gore Beat Bush, and Then Everything Changed: Stunning Alternate Histories of American Politics.

Listen to the episode here. There you can find two clips of our convo — on how dangerous a Trump reelection would be, and how Biden trapped us with terrible prospects against Trump. That link also takes you to a lot more reader debate over Gaza, with my lengthy replies.

Browse the Dishcast archive for an episode you might enjoy (the first 102 are free in their entirety — subscribe to get everything else). Coming up: Jonathan Freedland on anti-Semitism and UK politics, Nate Silver on the 2024 election, Christian Wiman on resisting despair, Justin Brierley on his book The Surprising Rebirth of Belief of God, Jeffrey Rosen on the pursuit of happiness, George Will on Trump and conservatism, and Abigail Shrier on why the cult of therapy harms kids.

Please send any guest recommendations, dissents, and other pod comments to dish@andrewsullivan.com.

Dissents Of The Week: Kids In The Crossfire

A reader writes:

Your latest column on the Israel-Hamas war is fundamentally unfair and, I must say, self-contradictory. You begin by making a powerful case against the “inflammatory, even grotesque” accusations that Israel is committing genocide. Then you make a 180-turn and level an even worse accusation against Israel: infanticide.

Andrew, do you know the meaning of the word “infanticide”? According to Wikipedia (and every other definitional source), it’s “the intentional killing of infants or offspring.” The word “intentional” is critical in defining infanticide, just as it is in defining genocide — the despicable conduct of which you simultaneously argue Israel is falsely accused of. Is that what you believe? That Israel is intentionally killing children?

How exactly is it not intentional? No, the IDF didn’t wake up one day and decide to murder a thousand innocents out of genocidal hatred. I made that point repeatedly. But they did wage a war they knew would disproportionately kill thousands of kids. The war was launched immediately; there was no safe location for children to be evacuated to at first; and then, when safe areas were demarcated, they were also bombed. Yes, Hamas could release the hostages and absolutely should. But you cannot wave away 500 2,000-lb bombs and thousands of child corpses, or lay all the blame at Hamas’ feet.

More dissents are here, along with my replies — same here, toward the middle of the pod page. A core point I make there:

I hope it’s clear I’m torn. I want Israel to not just survive but thrive; I despise Hamas; most of the world is posturing; but this war is an over-reach, discrediting, and needs to be directed to some sane goal. Right now, it appears it’s never going to end.

In The ‘Stacks

This is a feature in the paid version of the Dish spotlighting about 20 of our favorite pieces from other Substackers every week. This week’s selection covers subjects such as the Iowa caucus, the bleak prospects for Haley and Biden, and signs of democratic hope in Taiwan and Guatemala. Below are a few examples:

NS Lyons explains “the rise of right-wing progressives.”

The UK is banning ads showing — gasp — partial nudity.

Jesse Singal has a thorough takedown of the illiberal Atlantic piece that started the whole “Nazis on Substack” nonsense.

You can also browse all the substacks we follow and read on a regular basis here — a combination of our favorite writers and new ones we’re checking out. It’s a blogroll of sorts. If you have any recommendations for “In the ‘Stacks,” especially ones from emerging writers, please let us know: dish@andrewsullivan.com.

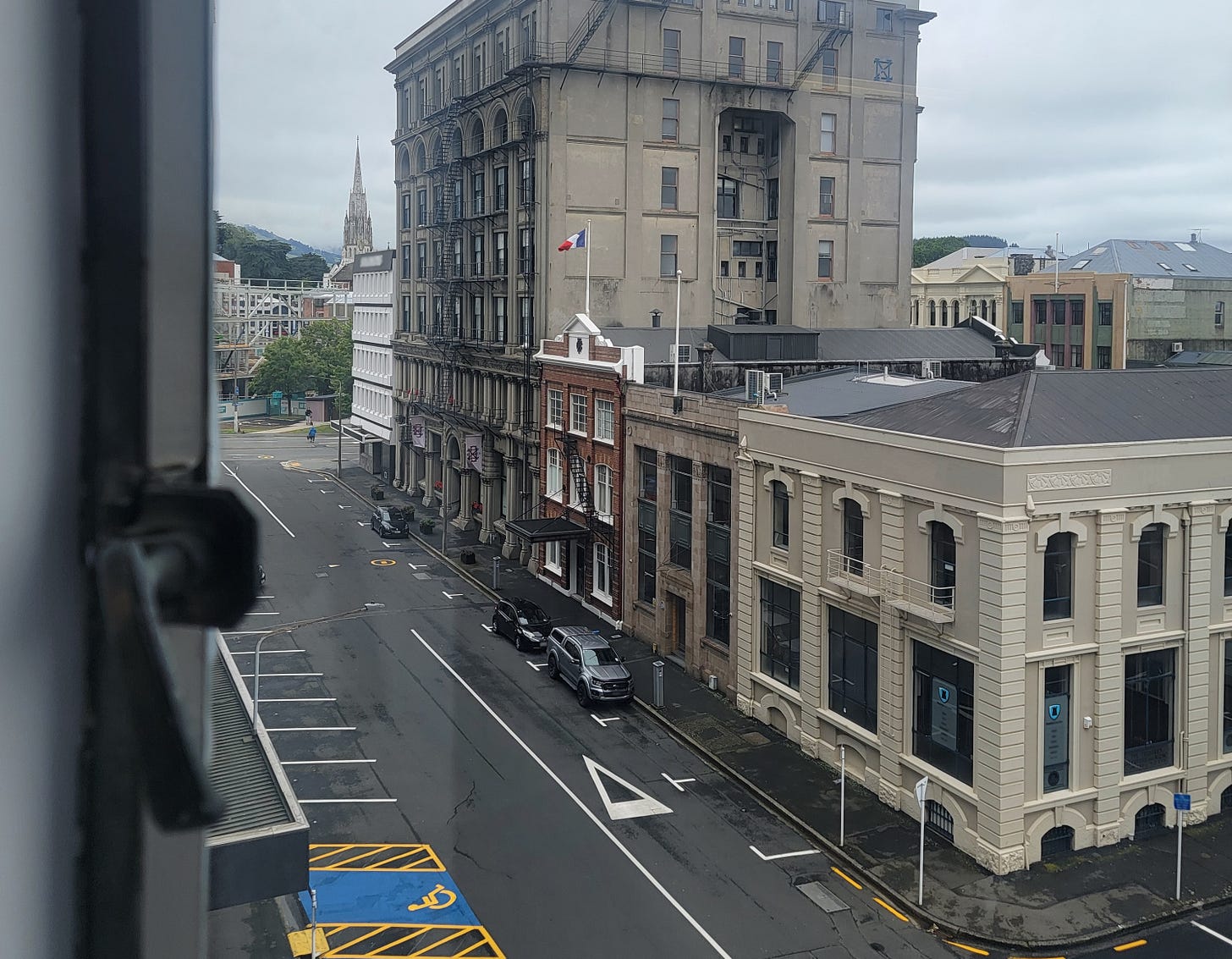

The View From Your Window Contest

Where do you think it’s located? (We erased the etchings on the closest building to prevent an immediate find.) Email your guess to contest@andrewsullivan.com. Please put the location — city and/or state first, then country — in the subject line. Proximity counts if no one gets the exact spot. Bonus points for fun facts and stories. The deadline for entries is Wednesday night at midnight (PST). The winner gets the choice of a VFYW book or two annual Dish subscriptions. If you are not a subscriber, please indicate that status in your entry and we will give you a free month subscription if we select your entry for the contest results (example here if you’re new to the contest). Happy sleuthing!

The results for this week’s window are coming in a separate email to paid subscribers later today. A teaser:

Well, it’s been over a year since my last entry. Yet, surprisingly, it only took about five minutes to solve this mystery. Upon finding the location, I sat in stunned silence at my impressive feat. “I AM A GOLDEN GOD,” I thought to myself. And then I realized this is probably one of the easy puzzles you throw out there every once in a while, so I’m guessing Chini got the correct answer two days before you sent out the picture.

Below is the bird’s-eye view from Chini (the grand champion of the VFYW for more than a decade), with the window circled:

See you next Friday.