Do All Black Lives Matter? Or Just Some?

On the soaring toll of civilian violence against African-Americans

“Papa, papa, don’t you cry. Today is not my day to die!” was one of Hamza “Travis” Nagdy’s favorite chants. A newcomer to activism, the 21 year-old with the big hair, broad smile, incipient mustache, and huge, sometimes raspy voice, became an inspiration to others in the Black Lives Matter movement in Louisville, Kentucky, this year.

In the wake of the police shooting of Breonna Taylor last March, Nagdy, we’re told, found meaning, direction and hope in channeling a community’s rage at police misconduct and apparent impunity. He had not had an untroubled life up to that point. “I told them two months before the movement, I was the closest I had ever been to committing suicide,” Nagdy told the Louisville Courier Journal in October. But then he led and corralled marches, took his megaphone everywhere, and organized a group called “Keep Going”, after words attributed (inaccurately) to Harriet Tubman: “If you see the torches in the woods, keep going. If there’s shouting after you, keep going. Don’t ever stop. Keep going. If you want a taste of freedom, keep going.”

In late September of this year, Nagdy addressed a crowd in the wake of the news that the police officers responsible for Taylor’s death were not being charged for killing her. It was a big step. “I could’ve just not been here, straight up, I could’ve just not been here,” he later said. “I came out to protest, just observing, watching, using a megaphone whenever I could. ... There was just so much beautiful interaction that happened that it made me realize that what was going on out here was building something different, and it gave me a reason to live.”

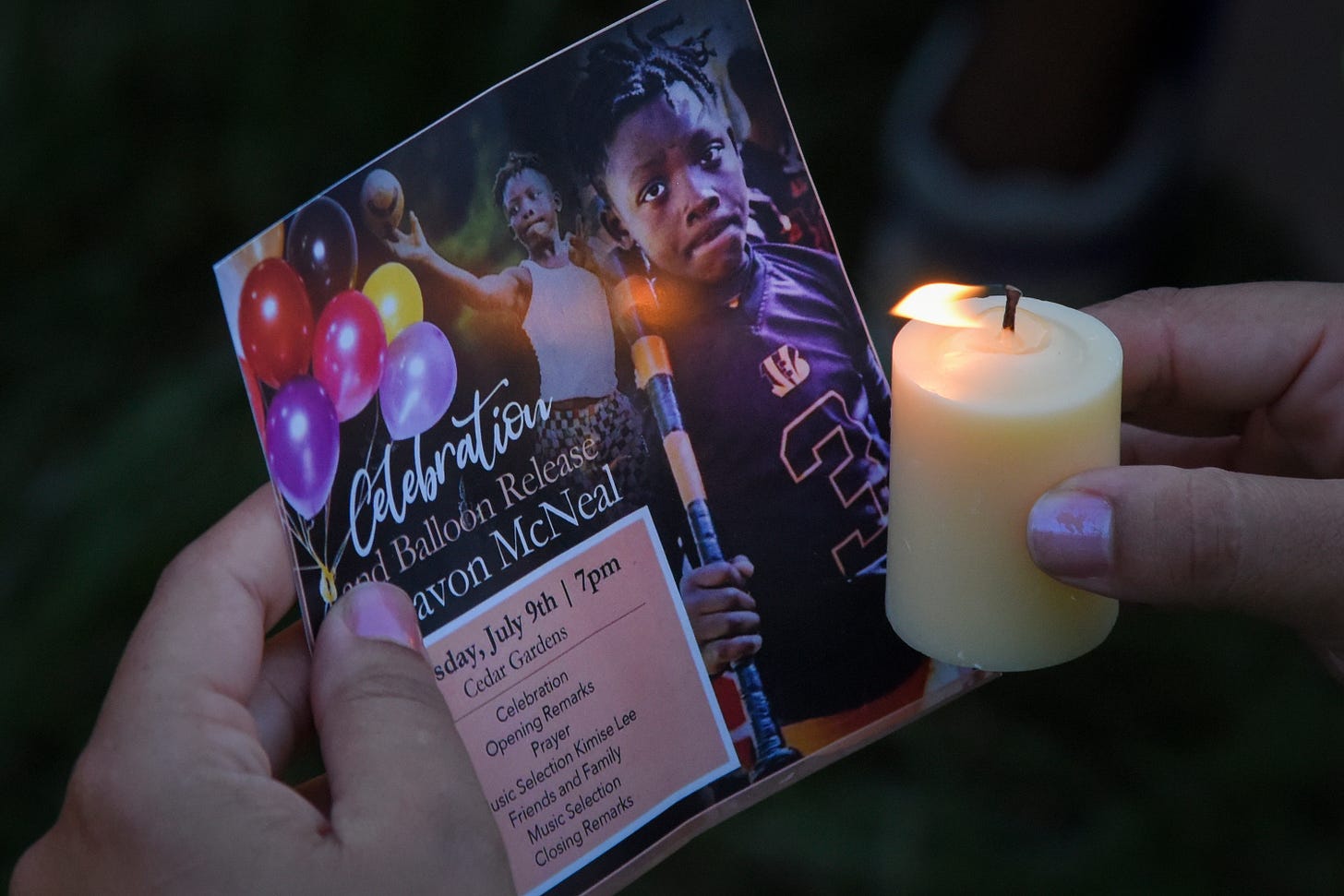

But he was not allowed to live. Nagdy was shot dead about a month after he made that statement to the Courier Journal. He was killed November 23 in what his mother described as a carjacking incident — and no one has been arrested yet for his murder. In this, he was far from alone. This year, between June 1 and August 4 in Louisville, there were 58 carjackings — up from 14 in the same period in 2019. Almost one a day in what the Courier Journal calls “a record year of gun violence in Louisville that has disproportionately affected young black men.”

And Louisville is not an exception to this wave of carnage. In Minneapolis, where the police killing of George Floyd occurred on May 25, the homicide rate has since soared. According to the Star-Tribune last month, “the 74 homicides this year are the third-highest total in the city’s history.” Again, carjackings feature: “Within a one-hour period Saturday morning, police reported three separate carjackings in southeast Minneapolis, including one where an elderly woman was struck on the head. Such attacks are up 537 percent this month when compared with last November.”

Who are the victims? They span the population, but the young and the black too often bear the brunt. In North Minneapolis, which is predominantly African-American, “the scores of victims have included a 7-year-old boy, wounded in a drive-by shooting; a woman who took a bullet that came through her living room wall while she was watching television with her family; and a 17-year-old girl shot in the head and killed.”

Nationally the toll on black lives from violence is shockingly disproportionate. The data from 2019 show 7,484 homicides of African-Americans, compared with 5,787 homicides of whites. That we have become used to this discrepancy doesn’t make it any less awful: African-Americans form only 13 percent of the population and yet comprise 54 percent of homicide victims. If you look at black men alone, it’s even worse. They comprise less than 7 percent of the population and a whopping 46 percent of the murder victims. Black men, in other words, are over six times more likely to be killed than the general population — and young black men face even worse odds.

Increasingly black children and minors are victims as well. This summer saw a horrifying killing of a one-year-old in Brooklyn in a stroller, in a shooting at a cookout; of an 11-year-old in Washington DC, who was also at a BBQ — this one part of an anti-violence event; and an 8-year-old girl in Atlanta, shot dead in a car near a Wendy’s. All African-American. In New York City alone, this year, seven children under the age of nine have been shot dead.

It is not therefore an exaggeration to say that African-Americans are being gunned down in America vastly out of proportion to their numbers in the population as a whole. We’ve heard this truth before, of course, but usually when talking of police shootings. And it’s true that police disproportionately kill black men — 26 percent of fatal police shootings are of black men, compared with their 7 percent of the population as a whole. This is a vital, troubling issue that deserves attention. But the disproportion for African-Americans killed by civilian shootings is almost twice as skewed as that for those killed by cops.

And the scale of it is on an entirely different level. In 2019, 243 black men (including only 13 unarmed black men) were shot dead by cops. In comparison, a whopping 7,484 were killed by civilians. If you believe that black lives matter, where is the outrage about that 7,484? If Travis Nagdy, a young man of color, had been killed by a cop, you would know his name by now. Because he was killed by a civilian, you probably don’t.

Yes, I know. A killing by a representative of the state is a much, much graver offense than that by a fellow civilian. We should take it much more seriously than regular crime. That’s why I favor every measure to increase accountability from the police — tackling their unions, de-militarizing their equipment, ending qualified immunity, putting more resources into de-escalation training, and so on. Nonetheless, a murder is a murder. A grieving mother and family is a grieving mother and family, regardless of who the killer is. And when the likelihood of an African-American being killed by a civilian is almost thirty times the likelihood of being killed by a cop, it seems to me perverse that almost all the attention is on the police.

It’s even more perverse to respond to this by calling to abolish the police altogether. In order to tackle three percent of black lives lost, you favor removing the primary force trying to prevent 97 percent of them! However problematic the police, what kind of practical sense does that make? And the immediate results in a city like Minneapolis show just how reckless — how deeply dangerous to black lives — this kind of strategy is. Demoralized cops are quitting in droves; gangs are re-taking the streets; neighborhoods are becoming war-zones.

Yes, I know many now insist that abolishing or defunding the police is not their real agenda. And for some, that may be true. But the record is quite clear: abolition of the police and of incarceration was exactly what many BLM activists and critical race theorists demanded, and still demand. It’s what the Minneapolis City Council voted for last June. It’s what Ilhan Omar explicitly demanded. It’s what the autonomous zone in Seattle enforced. It’s what BLM’s DC branch explicitly endorsed. It’s what the newly elected congresswoman Cori Bush supports. It’s what was painted on the streets of DC in letters large enough they could be read from an airplane. Abolition, in fact, is integral to critical race theory, and its view of the police as mere extensions of “white supremacy”, even when police departments are often very racially diverse or majority black, and run by black police chiefs.

It is no accident that the killing of George Floyd prompted a massive outpouring of protest while no such national movement emerged in response to, say, the killing of a one-year-old child in Brooklyn. Black lives matter, it seems. But some black lives matter more than others — depending entirely on who took them.

This left-progressive view is not one shared by most African-Americans. Or, for that matter, by leading and successful black pols like Barack Obama and James Clyburn and the late John Lewis. Polling in 2018 showed that only a small minority — 18 percent in one survey — opposed hiring more police officers, while 60 percent want more cops and more funding. A Gallup poll this summer found that “61 percent of Black Americans said they’d like police to spend the same amount of time in their community, while 20 percent answered they’d like to see more police, totaling 81 percent. Just 19 percent of those polled said they wanted police to spend less time in their area.” So mostly white leftists last summer campaigned for something a hefty majority of actual African-Americans oppose. And, of course, it is the African-American community that endures the murderous consequences.

The notion that the cops are universally reviled in the African-American population is just as false. In a Vox/Civis analysis poll, 58 percent of black Americans said they have a favorable opinion of their local police. In the Gallup survey, 61 percent are “very confident” or “somewhat confident” about “receiving positive treatment” by police. That’s much lower than it should be. There remains a real problem with police interaction with African-Americans. There is more to police misconduct than shootings — and some police departments are indefensible, as we saw most graphically in Ferguson. But that’s not an argument to defund or abolish the cops; it’s an argument to investigate and hold the miscreants responsible; and to reform, retrain and invest in the overwhelming majority doing their best.

If black lives matter, all black lives matter. If we feel agony and grief at a video of a black man killed by cops, we should also feel agony and grief when far more are gunned down by civilians with no video to show it, when law-abiding African-Americans are blindsided by carjacking and murder, when the fear black citizens feel when cops are around is dwarfed by the terror when cops are absent.

Funding and reforming the cops stands a much better chance of reducing the toll in black America from both cops and civilians than defunding, demonizing and demoralizing them. This may not satisfy those who are on an ideological crusade against “whiteness”. But if black lives really matter — and they do — all of them matter. And it’s worth re-upping our efforts to see the background noise of disproportionate black death as the national emergency it is.

(Note to readers: This is an excerpt of The Weekly Dish. If you’re already a subscriber, click here to read the full version. If you’re not subscribed and want to read the whole thing, and keep independent media thriving on Substack, subscribe now! This week’s issue includes a lengthy response from Katie Herzog to a reader dissent over her guest-column on the disappearance of lesbians; many personal stories from other readers on the topic; more window views, a hilarious Quote for the Week about a gay orgy, a Creepy Ad Watch for the holiday season, lots of recommended reading, a Mental Health Break from the surreal streets of Istanbul, and a new challenge for the View From Your Window Contest. Subscribe for the full Dish experience!)

New On The Dishcast: Olivia Nuzzi On Covering Trump

Olivia is the brilliant 27-year-old Washington correspondent for my old haunt, New York Magazine, who has been covering all things Trump. I talked with her about the man who has defined so much of the news these past five years.

To listen to two excerpts from our chat — on the first time Olivia met the failed casino tycoon; and on whether Trump is a germaphobe or just a snob to the unwashed masses — head over to our YouTube page. Listen to the full episode here.

As always, keep the reader dissents coming, along with anything else you want to add to the Dish mix, such as a view from your window: dish@andrewsullivan.com.

See you next Friday.