The Tao Of Marty

Marty Peretz's memoir — and a story of American liberalism.

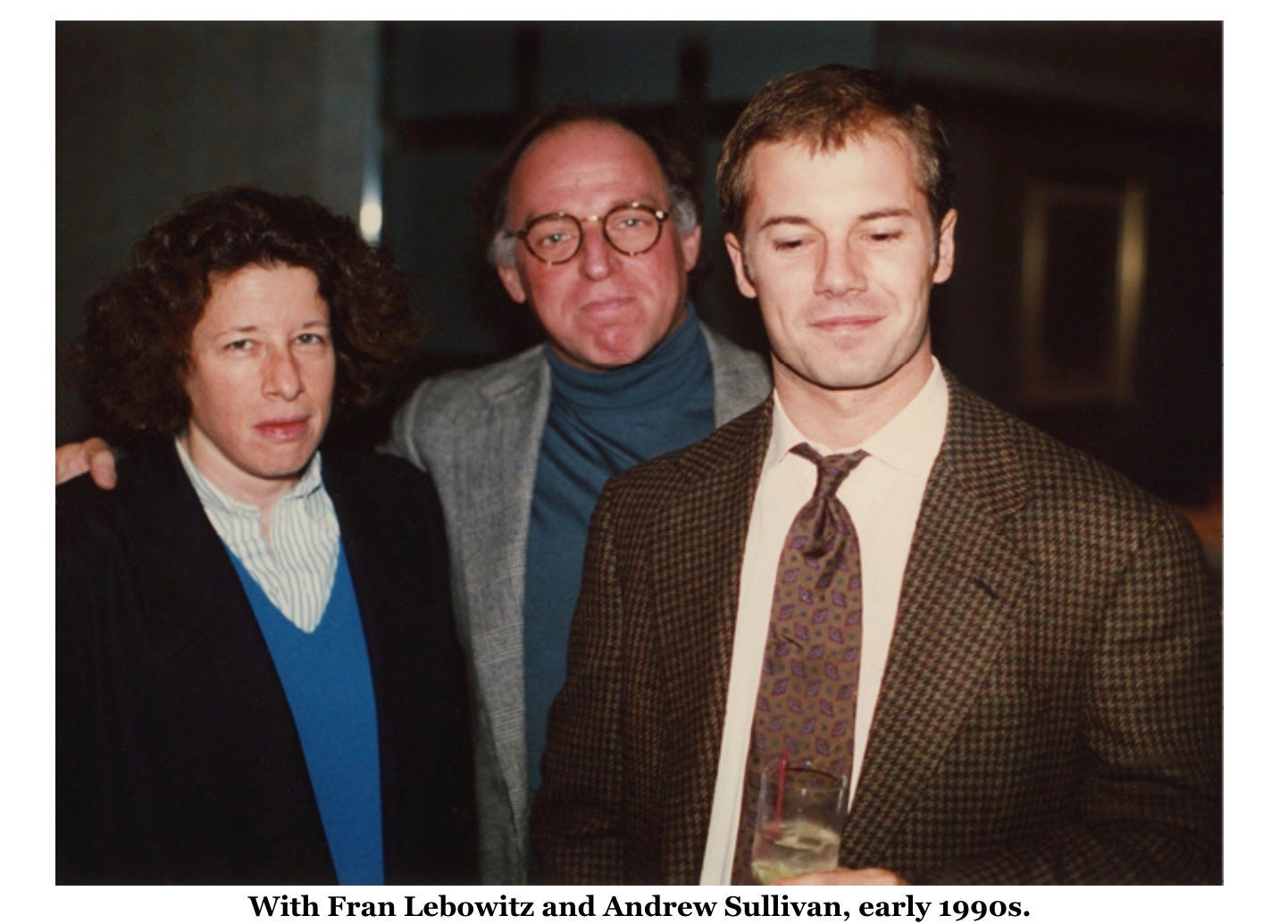

I first met Marty Peretz in Cambridge at the Coffee Connection — a Starbucks before the Starbucks era — when I was starting my graduate studies at Harvard. He’d been invited to the Oxford Union to debate the Israel/Palestine question, and the Union president of the time, Larry Grafstein, had called me up and asked me, as a former president, to give this man a briefing on what to expect.

I didn’t know what to expect with “Marty” either, and was still a bit baffled by him not being known at least as Mr Peretz. And when he showed up, he looked like someone I’d only ever seen in a Woody Allen movie: a huge rabbinical beard, a blousy shirt unbuttoned to near his navel, a Star of David necklace buried in chest hair, a gravelly voice and a mischievous grin. When he told me he was defending Israel at Oxford, I told him he was fucked, but not to worry. He’d lose the vote, but he should go down blazing anyway. Go for it, I advised. Fuck ‘em. (And in the end, in fact, his side won.)

There I was, this tiny, obliviously pretty, Catholic, Thatcherite gay boy from a small English town, just off the boat in a way, and here was this cosmopolitan macher of machers, son of a family slaughtered by the Nazis, Harvard impresario and elite networker, Civil Rights Movement hero, and magazine mogul, convening over a latte … as equals. Or that’s how it felt.

He never taught me social studies, but I saw instantly why he was prized by his students (many of whom went on to run the country in one way or another): he didn’t patronize, he didn’t rest on authority, and he actually seemed interested in you. And though culturally light years apart, it was instantly clear we had something in common: we loved an argument. And by argument, I don’t merely mean merely the activities of the mind, but of the heart and the soul. I mean passion, fun, and occasionally fury. I mean the occasional willingness to go down fighting.

And I have to say I was a little nervous about his new memoir, The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone, Left Right and Center, as anyone who knows they’ll be written about in someone’s memoir might be, but I soon forgot about that as I started reading. The story is a deeply, fascinatingly American one. A parvenu, Brooklyn-born, Brandeis-educated Jew who became a “Harvard patriot” in his words, Marty bought The New Republic in 1974, and he turned it, for three decades, into essential reading.

His earliest influences were Herbert Marcuse, believe it or not, and Max Lerner, whose Jewish Americanism provided a kind of template for his life: “I was Jewish and American at all times, and there was no contradiction between those inheritances.” Marty is that rare combination: a tribal anti-tribalist, without qualms. Here is how he describes his Jewishness: “It’s a force in me — not a belief, a force — so strong, so roughly and deeply sensed, that it obviates contradictions with which other people grapple.” That’s as honest and revealing as the rest of the book.

Although the far left regards him now as some kind of reactionary, his liberal credentials, as you’re reminded here, are hard to impeach: working with Bayard Rustin preparing for the 1963 March of Washington, and then, with his second wife’s large fortune, financing and organizing the anti-Vietnam movement, pioneering the Eugene McCarthy campaign that caused LBJ to drop out of the race after New Hampshire, and trying to forge a synthesis of the civil rights and the anti-war movements by organizing the ill-fated National Conference for New Politics in 1968.

That year, of course, was the critical moment when the old Jewish-black Democratic coalition fell apart, and Marty’s world shifted. Planning for the conference was held at Marty’s rented place in Wellfleet:

One night, after most people had gone back to their motels, I came downstairs to find blacks and whites together on my porch singing anti-Semitic songs about Jewish landlords overcharging and evicting black tenants in Harlem. Most of the whites singing were Jews, and I could see they were enjoying a kind of vicarious thrill, a subversive titillation, that went through them as they sang. I threw them off the porch.

The whole incident is a kind of metaphor: what happens when a left-liberal alliance degenerates into left-illiberalism. It’s where we are again today, with the totalisms of critical race, gender and queer theory displacing the much more limited and humane principles of gradualism, reform and liberalism.

Marty is and was vital to creating the intellectual conditions for the center-left’s revival in the Clinton-Gore and Obama-Biden years. He was also a critic of both, of course. In 1991, The New Republic helped launch — and occasionally attempted to rescue — the Clinton campaign, as I was seduced by Bill’s charm and pragmatism, and Sidney Blumenthal became their loyal and elegant stenographer. Al Gore had long been one of Marty’s favorite students, and he went on to become the vice president. No wonder some wag dubbed us “the in-flight magazine for Air Force One.”

And yet we then helped torpedo Hillarycare, proposing something more modest that, in the end, looked more like Obamacare. And we went after President Clinton on gay issues; and his sickening treatment of women. (We were one of the few liberal outlets to urge that Paula Jones be given her day in court.) Marty also disdained Obama’s foreign policy, of course. He saw in it a kind of know-it-all universalism. Marty had always been different: “I understood the realities of tribes, nations, and peoples.”

A racist? Please. This was the man whose magazine published Skip Gates and Stanley Crouch, Derek Walcott and Glenn Loury, Amartya Sen and Anita Desai, Albert Murray and Wynton Marsalis. What he couldn’t stand was the pious bullshit of the “anti-racists” of his time, their blindness to complexity, their refusal to grapple with black family breakdown, the paradoxes of welfare, the importance of fatherhood, and the bigotry of their low expectations.

An obsession with Israel and a near-adamant refusal to call the Jewish state to account? Sure. To put it mildly. It’s where we eventually differed — over the Netanyahu government’s shabby treatment of Obama, and the US-assisted suicide of the two-state solution. But I always saw Marty’s rigidity on this as more a function of passion than fanaticism, driven more by love of Israel than hatred of its enemies. But yes, at times, it was close.

In picking me to be editor, and in allowing me to write graphically about the AIDS epidemic, and in favor of marriage equality, in the 1980s and 1990s, he was brave. I didn’t know at the time, and he never told me, but he was closeted in a straight marriage. The overwhelming majority of closeted men back then wouldn’t touch the gay issue with a ten-foot pole, for fear of being seen as gay themselves. But Marty went there, and stood by me — the only openly gay journalist in DC — and stood by the work we did in bringing gay rights back to the liberal and conservative center — the platform for future success (now, of course, threatened with reversal by the transqueer left and Christianist right).

Marty was there when I tested HIV-positive as editor, and I faced the prospect of deportation and an early death, even as I worked to put out the magazine every week. He never wavered. He helped me find doctors and lawyers. He kept me on health insurance after I quit the top job. These private kindnesses were legion — I was just one of the people he cared for. He was a Mensch (others weren’t), and I will never forget it.

And what he conjured in The New Republic’s glory years was unique: internally contentious, unpredictable, passionate, literate, funny and ballsy. Leon Wieseltier, Charles Krauthammer, Michael Kinsley, Rick Hertzberg, Bob Wright, Mickey Kaus, and Michael Lewis, each a generational genius in his own way, were just part of the chemistry. The interns were fully a part of the editing and debating in a genuinely democratic process. And much of the energy was driven by a contempt for the extremes of right and left, and a love for debate — even when it left bruised egos and ended friendships.

At the end of the five years I was editor, we reached 100,000 readers and a tiny profit. And we were never being boring. The viciousness of the subsequent attacks by the woke left on the magazine in that era is testimony, I’d say, to the impact we had. And to the abiding jealousy that its success evokes.

There’s some good dish in the book: who else spent two hours trapped in an elevator with a chain-smoking Salvador Dali? Or spent a flight talking to a literate Englishman he didn’t recognize, only to find out later it was Mick Jagger? Who else could bring Alger Hiss, Lillian Hellman and Roy Cohn to Harvard for his seminar? Who else could say of Norman Mailer: “In real life, I liked him because he saw me so clearly. He knew I was gay; I don’t remember how, since I wasn’t so gay then.” In their last encounter, in a Provincetown restaurant, Mailer punched Marty in the stomach, after the magazine had torn his latest novel to pieces. Those were the days.

And there are a few really good jibes: “That was the other thing I liked about [Fidel] Castro: he was an adversary of the Kennedys.” Here’s his take on Jim Fallows: “a gentle and righteous sop for whatever establishment thinking was at in any given moment.” On Wieseltier, once Marty was no longer of any use to him: “He was still Leon, only more confident in his evasions: he wouldn’t call you back if you needed something from him, but if he needed you, he’d call you in the middle of the night.” On Hannah Arendt: “Ordinarily, a highly esteemed thinker who bedded down with a Nazi and carried on with him after the war might have been expelled from high-minded intellectual circles. But curiously, that was not the case here.”

This book is not revenge on anyone. It’s not a diatribe. It’s elegantly, sometimes beautifully written, and brutally self-exposing. He acknowledges his mistakes, confesses his sins, and holds himself to account: “The logic I grew up with and operated on was sound, until the point it wasn’t.” He writes of early crushes on his male peers; he is poignant in taking responsibility for the end of his remarkable marriage to a remarkable women, Anne; he evokes his terrifying father; and he writes honestly about the core fight around publishing a symposium on The Bell Curve:

Leon said: Publish a review of the book but don’t run the piece itself. We don’t run Marxists here; we shouldn’t run Social Darwinists. Andrew said: Our readers read Marxists and Marxist derivatives already. If we don’t run Murray they’ll never read him at all — and Murray is a person who matters.

I was speaking about my own ignorance as well: reading the draft of the book was the first time I’d ever even heard there were racial differences in the distribution of mean IQ. That forbidden knowledge — uncontested, uncontestable — was something we needed and need to know. Because it was and is real. That’s all. Why it was real and how to fix it were open questions. And the ongoing debates over the fraught issue are still necessary, which is why the woke left wants to render them entirely taboo — along with countless of their other stagnant little orthodoxies. Our job as writers, I believed, was to open up debate with epistemic humility, courage and precision; it was not to shut it down in a flurry of virtue-signaling.

You can dismiss my praise of this book as a helpless conflict of interest, of course. Fair enough. But trust me, if this book were crap, I’d say so, and Marty would eventually understand (after a couple of irate phone calls). But it is, in fact, a candid snapshot of American political and cultural history: lively, literate and easy to read.

What it also conveys is what I consider to be Marty’s greatest strength, despite his many failings, his anger, his pugnacity, his sometimes self-defeating insecurity, his long-lived grudges and blow-ups. Marty is a lover, first and foremost. Those of us who have been recipients of this love can testify to its power and generosity. This is the truest part of the book:

I was happy to be disconcerting and answer only to myself. I was happy to love people without conditions, or many conditions, and to act on that love. There’s a lot of tenderness in me: it’s easy, a friend once told me (this was after I’d talked him through his second divorce), to get into the loam of my heart.

It is. After all the tempests and fights, dramas and wars, seminars and articles and cover stories, after disillusionment and pain, cancellation and renewal, divorce and coming out, Marty’s journey proves what Larkin called our “almost instinct almost true.”

What will survive of us is love.

(Note to readers: This is an excerpt of The Weekly Dish. If you’re already a subscriber, click here to read the full version. This week’s issue also includes: a discussion of “filthy rich politicians” with Matt Lewis; dissents over my view of Biden as a normal president; seven notable quotes from the week in news, including an Yglesias Award on free speech; 26 links to Substack pieces we enjoyed on a wide range of topics; a Mental Health Break of an AI-generated trailer for Barbenheimer; a heavenly window from the Austrian alps; and, of course, the results of the View From Your Window contest — with a new challenge. Subscribe for the full Dish experience!)

From a Dishhead who maintained his subscription through our renewal period:

Thank you for another wonderful year of wrestling through so many challenges. I moved, took a new job, and did a lot of personal-growth work, and I am thankful that I have the Dish to keep me thinking. I don’t write in much because of my job in public service, but I do appreciate being part of this unique community.

From another re-subscriber: “I haven’t traveled much, so it’s a real treat to follow all the fascinating entries in the VFYW contest!”

New On The Dishcast: Matt Lewis

Matt is a political journalist. He’s been a senior contributor for The Daily Caller and a columnist for AOL’s Politics Daily, and he’s currently a senior columnist at The Daily Beast. He also hosts his own podcast and YouTube show, “Matt Lewis & The News." In this episode we discuss his new book, Filthy Rich Politicians.

Listen to the episode here. There you can find two clips of our convo — on the perception of insider trading in Congress, and how Palin paved the way for Trump. That link also takes you to a bunch of listener debate on last week’s episode about Gen Z.

Browse the Dishcast archive for another conversation you might enjoy (the first 102 episodes are free in their entirety — subscribe to get everything else). Coming up: Lee Fang on the tensions within the left, Josh Barro defending the Biden administration, and Michael Moynihan on general kibitzing. Please send any guest recs and pod dissent to dish@andrewsullivan.com.

Dissents Of The Week: Normal Compared To What?

Pushing back on my column portraying the Biden presidency as “normal,” a reader writes:

When you say inflation is down to 3%, remember that is “Core CPI,” which leaves out food and energy. Well, the lower down the income scale one goes, the higher percent of one’s budget is spent on food and energy. Besides, compared to 2020, gasoline is still up 50%. Electricity is up 26%. Food is up 17%. Want to talk about used cars? And don’t get me started on home prices, where young families increasingly find themselves bidding against corporate investors, who are buying a quarter of all single-family homes on the market.

Alright already. Point taken. And the excesses of the spending bills doubtless exacerbated inflation. But which other Western nation would you rather be at this moment?

I respond to more dissents here. Keep ‘em coming: dish@andrewsullivan.com. Follow more Dish discussion on the Notes site here (or the “Notes” tab in the Substack app).

In The ‘Stacks

This is a feature in the paid version of the Dish spotlighting about 20 of our favorite pieces from other Substackers every week. This week’s selection covers subjects such as the end of cash bail, Therapy Inc., and the prosperity gap between the US and Europe. Below are a few examples, followed by new substacks:

Sam Kriss sends a searing dispatch from an elite party of British pols and journalists: the famed, annual Spectator garden party.

Lucy Webster writes about swimming with cerebral palsy.

Tech journo Alexis Madrigal dips his green thumb into Substack. Welcome! And godspeed to Feminists for Liberty on their new zine.

You can also browse all the substacks we follow and read on a regular basis here — a combination of our favorite writers and new ones we’re checking out. It’s a blogroll of sorts. If you have any recommendations for “In the ‘Stacks,” especially ones from emerging writers, please let us know: dish@andrewsullivan.com.

The View From Your Window Contest

Where do you think it’s located? Email your guess to contest@andrewsullivan.com. Please put the location — city and/or state first, then country — in the subject line. Proximity counts if no one gets the exact spot. Bonus points for fun facts and stories. The deadline for entries is Wednesday night at midnight (PST). The winner gets the choice of a VFYW book or two annual Dish subscriptions. If you are not a subscriber, please indicate that status in your entry and we will give you a free month subscription if we select your entry for the contest results (example here if you’re new to the contest). Happy sleuthing!

The results for this week’s window are coming in a separate email to paid subscribers later today. From last week, here’s a sleuth in San Francisco:

The last six weeks have been a blur of travel (visiting mom in Hawaii) and moving (still in San Francisco), which has cut into my VFYW sleuthing time. Most weeks, I study the photo for a bit and come to an initial conclusion about where it might be — but then stop. Last week, though, I initially concluded that the city in the background was Cebu and that the photo had to have been taken from one of the resorts on the east side of Mactan Island in Lapu-Lapu. Why did I think that? Because I’ve been there.

So what did I do? I consulted with my beautiful bride, who happens to have been born and raised in Lapu-Lapu. And when I say beautiful, it’s not just my bias speakin: she freaking won the Miss Lapu-Lapu beauty pageant when she was 19! So I showed her the photo and said, “Isn’t that Cebu in the background? Do you recognize the weird building in the foreground? Can you read any of those signs?” … eagerly awaiting confirmation that I was right.

She studied the photo for a bit and then said, “No, we don’t have that in Lapu-Lapu.” I was crushed. I told her later that the photo was taken from the Jpark resort and she said, “Huh, that’s the only one I haven’t been to.” Just my luck.

We have been back to Lapu-Lapu a few times and have stayed at a number of other resorts just up the coast from the Jpark (Crimson, Shangri-La, Movenpick), so I’ve probably driven by the Jpark more than once. But one of my favorite Lapu-Lapu things to do is to attend the Kadaugan sa Mactan, a food festival that takes place at the Mactan Shrine where the statue of Lapu Lapu himself is located and where the story of his victory over Magellan is depicted. All the local hotels and restaurants set up food booths, so you can wander around and stuff your face for hours. Maybe our super-chef will have an opportunity to partake some day.

Anyway, here’s me at the statue trying to look warrior-like:

Here’s a portrait of the lovely couple from contest #324 in Vegas:

See you next Friday.