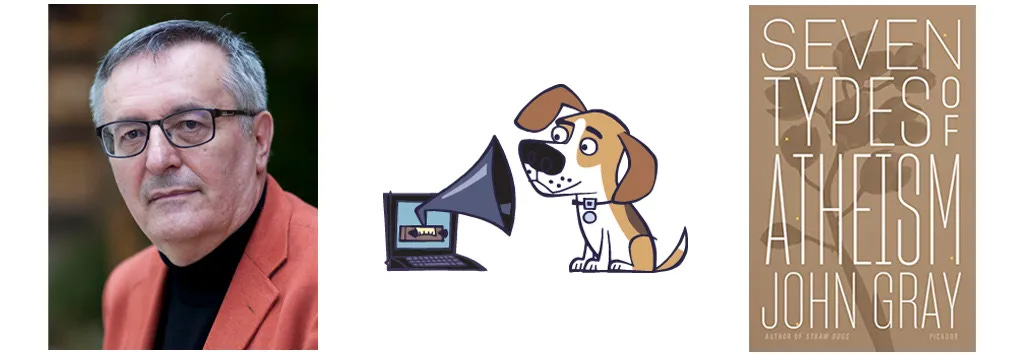

Transcript: John Gray On The Dusk Of Western Liberalism

The great philosopher - unfiltered, funny and fierce.

John Gray is a political philosopher. He retired from academia in 2007 as Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics, and is now a regular contributor and lead reviewer at the New Statesman. His forthcoming book is The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism. I regard him as one of the great minds of our time, and this is one of my favorite pods ever.

The episode originally aired on March 3, 2023. Some money quotes from John:

“Politics is a succession of temporary and partial remedies for recurring human evils. So rather than getting hung up on one particular project or fashion or doctrine — or worse still, ideology — you should look at the biggest evils of your time and what can be done about them.”

“Populism is a term liberals use to describe the political blow back against the social disruption that their policies have created.”

“The essential point of enlightenment thought is that there isn’t evil — there’s just error. There are just people who make mistakes and they learn from them.”

Andrew: Hi there and welcome to another Dishcast. We've had such amazing feedback from last week’s with Aurelian Craiutu on moderation. Really inspiring to know that we can do really quite high-level stuff here and people really enjoy it and appreciate it.

That's one reason I'm incredibly psyched today to have a writer and a philosopher that I've followed — and known, a little — for many years, going all the way back to Harvard actually. His name is John Gray. He's a political philosopher if you haven't heard of him.

He retired from academia in 2007 as School Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics and is now a regular contributor and lead reviewer at The New Statesman. If you haven't checked out his reviews, they're really terrific.

His many books include False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism, Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia and Seven Types of Atheism. That's another really fun read. His latest is Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life. And he has just put on its way a magnum opus on Hobbes and the end of liberalism or what happens after liberalism. He is very hard to characterize in so many different ways, but a wonderful conversationalist and a wonderful thinker.

I just want to let you know, before we get going, about some of the amazing people we have coming up. We have Michael Lind coming on the show. We have James Alison, the Catholic theologian. John Ward, the fundamentalist — he's an evangelical, I shouldn't say quite fundamentalist. He's an evangelical. He's a wonderful person. He's coming to talk about his experiences of the evangelical movement as it came under the influence of Donald Trump. And John Oberg, the vegan proselytizer. He is going to try and talk me into giving up meat. And Cathy Young, we're going to hash out some of the Ukraine stuff and also some of the questions about higher education, and how we actually maintain some kind of diversity of thought in our educational structures.

But on to today. It's a beautiful day here. And John, it's lovely to see you again. And thank you for coming on the show.

John: Thank you for inviting me, Andrew, and great to see you again.

Andrew: John, tell me and tell us — you grew up in the north of England, but in South Shields, which is near Newcastle.

John: South Shields was then a working class industrial town. I grew up in a working class street community in South Shields, a town which is now and began to be in, I would say the '60s and '70s, post-industrial. So most of the industries that people I grew up with worked in — coal mining, ship building — have gone. But when I grew up in it in the 1950s and '60s — I was born in 1948 — it was still a town of working class street communities. And I grew up in one, which meant I grew up in a strong and cohesive community which had never heard the word "community."

Andrew: Which of course is definition of a real community. [laughs]

John: It is, they never talked about it. They probably didn't even have the concept of it, but they were in one. And this is not urban folklore. I experienced it. Front doors weren't locked. There was practically zero street crime. There certainly wasn't the random violence that one finds in many urban settings today. It just didn't exist.

Of course, in other ways it could be restrictive because it was highly cohesive. It wasn't ethnically homogenous. There was a longstanding Yemeni community, but it was quite restrictive in the sense that there were common norms and if you didn't like them or didn't get on with them, the common thing, especially for men, was just to leave. So some would join the Navy, the merchant Marine, that was very common. And then later on, some of them left via education, which I did.

I went to a selective grammar school. And from that I went on, as others did, to university. In my case, Oxford. But that was a very profoundly formative experience for me, because I now realize what perhaps I didn't realize for a long time fully, that it shaped my beliefs and attitudes and even my philosophical outlook in certain profound ways.

Because what happened in the '60s and onwards, was that the material deprivations of these communities: outside toilets, no central heating, you bathed in a tinned tub, going to the loo in the middle of the night might be a rather icy experience in the winter. The reforms and initiatives that were introduced by the Labour government from 1945 to 1950, and then later on by various labor councils such as those in South Shields. These were part, I should say, of a government and a project in post-war Britain that, had I been adult, I would've strongly supported. My values then and now are still in many ways what are sometimes called old Labour values of solidarity and so on.

One feature I noticed then, which had a profound impact on me, was that when the street communities were leveled, demolished, and those who lived in them, including me, were moved out to orbital housing estates on the edge of town — not high rises, but housing estates. There was central heating and proper toilets, and all the material features of life were substantially improved.

They were settings in which the communities that had existed earlier, which were multi-generational, tightly-knit, mutually supportive, often rather matriarchal, by the way, despite the way they're often thought of, broke up. And within a year or two of being moved out, or even less than that, there was graffiti, there was street crime, there were all the pathologies of what sociologists call anomic individualism.

That led me to the following reflections, which stayed with me, although I didn't quite, as I say, realize that they were rooted in my childhood and early youth the way I now do. Which is that great advances — which I think is what that labor government of 1945 to 1950, that later on brought about — are often associated with losses.

This led me to my persistent skepticism, or as my critics would say, my persistent heresy about progress. There's a lot of shallow debate about progress. Is it inevitable? Oh come on, forget it. Do we never get to perfection? The key point is that we haven't got a coherent idea of perfection.

If you're a believer — I'm not — God can understand the perfect because God is himself or herself or itself, perfect. The way I thought about the error of progress or of faith in progress is not that it's not inevitable, or that we can't reach perfection, it's that all great advances, or many of them anyway, involve some great losses. Also the gains that are achieved in great advances are nearly always lost later. I'm talking here about advances in ethics and politics.

In science and technology there's a much more cumulative pattern. The science which is discovered doesn't completely reject the earlier science and it's not easily lost. Let me give you an example, relevant to what we'll be talking about later on I think about liberalism. If 90% of all the scientists in the world now disappeared in some terrible zombie plague, science I don't think would be wiped out. And it might not even take very long to start accelerating again. Science is preserved in libraries and now various forms of electronics.

Andrew: In the cloud.

John: In the cloud. It's all still there. And I think the survivors would rebuild it quite quickly and it would even become exponential, as it now has become. So in science and in technology, there's something like exponential progress, which means exponential advance. If all the liberal societies disappeared from the world, it wouldn't be like that. It would take much longer or never for them to be reconstituted or reassembled.

Now, this embodies an insight of Oakeshott's, which is that political life and traditions of thought and various abstract notions that we have about rights of liberalism, their roots are not actually in theories.Theories came later. They are practices.

If all the practices of liberalism vanished, and I think they are vanishing pretty quickly, quite a lot of them, actually. They won't necessarily restart. They won't necessarily start by themselves because they're embodied in human beings. When the human beings are gone, they're not just library books or the cloud, they're human practices, human beings.

Andrew: And this is a distinction that Oakeshott made actually, the distinction between programmatic and dramatic. In other words, that the agency that we humans have, the choices we have, allow us to make choices that are foolish and wrong.

It gives us a radical freedom both to create and to destroy. Whereas problematic stuff, just like science, you can actually project into the future the way things are going. That's never the case with humans.

John: I entirely agree. So what I took from my experience growing up in these communities, which then disappeared — a whole way of life disappeared in 15 or 20 years. An entire way of life disappeared. I mean, by the way, that doesn't make me a tragic figure, it makes me a very lucky figure because if you think of the 20th century, to be a survivor from a vanished way of life usually means genocide or murder or terrible warfare or something like that.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Weekly Dish to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.