“Preach the Gospel always. If necessary, with words,” - attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi.

“Every man and every woman must have a window in their life where they can turn their hope and where they can see the dignity of God. And being a homosexual is not a crime. It’s a human condition,” - Pope Francis.

I didn’t know much about Jorge Bergoglio when he first appeared on the balcony of St Peter’s. I didn’t realize he’d been a close runner-up to Josef Ratzinger, who had become Pope Benedict XVI in the 2005 Conclave. But just by his first words, I knew something had shifted. As we waited for his first blessing, he reversed the dynamic:

Let us make, in silence, this prayer: your prayer over me.

He asked us to pray for him. For a very long time — through the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI — the papacy had become a pillar of authority. Our duty as Catholics was to obey and revere the “Supreme Pontiff.” In Benedict’s words: “The faithful must accept not only the infallible magisterium. They are to give the religious submission of intellect and will to the teaching which the Supreme Pontiff or the college of bishops enunciate on faith and morals.”

Now, here was a man who referred to himself as merely a “bishop for the diocesan community of Rome” and who asked us, the faithful, to pray to God for him. He wore simple vestments, eschewing the intricate and fabulous outfits of his predecessor, remarking as he turned them down: “The Carnival is over.” After the flinty Pole and the prissy German, here, at last, was a warm Italian again, like John XXIII — even though he was from Argentina.

His voice was clear but quiet and softly pitched. And then, rather than assert papal authority as Benedict had done so often and so rigidly, he sought a simple moral authority — by embracing the grotesquely disfigured, listening intently to small children, washing the feet of male and female prisoners, eschewing the Papal palace for a simple apartment, and inviting transgender men and women on the streets to lunch with him in the Vatican.

Faith for Francis was not rigidity, it was not always certain, and it was not words. It was a way of life, of giving, of loving, of emptying oneself to listen to God without trying to force a conclusion — of discernment, as the Jesuits like to say. He later told the story of how he accepted the papacy, and it still inspires me as a way of praying:

Before I accepted I asked if I could spend a few minutes in the room next to the one with the balcony overlooking the square. My head was completely empty and I was seized by a great anxiety. To make it go away and relax I closed my eyes and made every thought disappear ...

I closed my eyes and I no longer had any anxiety or emotion. At a certain point I was filled with a great light. It lasted a moment, but to me it seemed very long. Then the light faded, I got up suddenly and walked into the room where the cardinals were waiting and the table on which was the act of acceptance. I signed it.

The church needs doctrine, it needs an infallible magisterium, and those who want this to suddenly change are guilty of a category error. Francis didn’t change an iota of doctrine, to some “progressive” dismay. But he did something more important. He reminded us that doctrine without love is what Jesus rejected.

And he insisted that faith without doubt was not faith at all:

In this quest to seek and find God in all things there is still an area of uncertainty. There must be. If one has the answers to all the questions — that is the proof that God is not with him.

For those who seek in Catholicism a psychological, intellectual, and even political anchor, Francis was maddening. He told them not to be so certain. He told them there was room for dialogue, that the clergy were too full of themselves, and that there were no areas where conversation could not happen. There was divine truth and then there was the mess of human existence, and the church was about where the two meet, denying neither, a field-hospital full of groans and blood, not a pristine, distant, well-kept Cathedral. After the authoritarian papacies of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, it felt as if window had opened and the fetid air banished.

That meant at times an unsatisfying lack of resolution — which some believe is harmful to the faith. On gay men and lesbians, on communion for divorced couples, on transgender people, he did not overturn doctrine, but he removed stigma. He encountered us with love first of all. He was about patiently untying knots, not making them even tighter. “If the Christian is a restorationist, a legalist, if he wants everything clear and safe, then he will find nothing,” he said.

When he emerged as Pope, I was in a sustained crisis of faith. I had discovered in the Church I trusted a depraved evil in the sex abuse crisis that still haunts me. As a gay kid who loved my faith and tried as I grew up to reconcile my own nature with its strictures, I had endured and argued and in good faith tried to understand.

And then I discovered it was all a sham; the pastor of my own parish in DC, Cardinal McCarrick, turned out to be a serial abuser and a closeted gay man, like so many others. Or rather they were not gay men as I knew them, but warped, psychologically stunted pedophiles and pederasts whose internal pain had morphed into patterns of abuse and concealment and astonishing hypocrisy. And after the callousness with which Benedict had treated the AIDS crisis, and his description of me and those I saw dying around me as “intrinsically morally disordered,” I found myself in acute spiritual pain.

Why did I not leave? Simple really. Because I never lost my faith in Jesus or the Gospels or the Church itself, regardless of its all-too-human priesthood. In fact, I had found faith indispensable to surviving the devastating young death I saw all around me in my twenties and thirties and also faced myself. The hierarchy may have wounded me, but I knew and had been guided by many truly good priests, many wonderful lay Catholics, and, well, in the words of Saint Peter, where else would I go?

But the anger at the institution was so intense I found myself shaking at times in the pews, unable to focus. So I took some time away (I remember Christopher Hitchens’ delight when he found out). And when I returned, I went into a side-chapel at the Cathedral at Mass to square the circle somehow, to put a little physical distance between the faith and the morally tattered institution that nonetheless I believed and still believe is the authentic harbor of Christianity for 2,000 years.

The chapel was dedicated to Saint Francis, and I prayed to him every Sunday to help me. And so the very name Bergoglio chose as Pope spoke instantly to me, like a voice reminding me that I still belonged here. And then Francis’ transparent love for all of us, including homosexuals, disarmed me. Or more accurately, on a few occasions, it prompted me to break down and weep. If I was sincerely trying to follow Christ, Francis told me, he was not going to throw me out. It is hard to express what those simple words of human recognition and love did to me, after so many years. It was like a dam breaking in my soul.

I never expected the doctrine to change, because I’m a smart fellow, had read my theology, and was not entirely sure how it could. But I knew that in the long history of the church, gay men and lesbians had been always present, often central, to its liturgies, its monasteries and convents, its education and art and music and intellectual rigor. The more I learned about the past, the more the modern church’s fixation on sex and gay people seemed the exception and not the rule. There was a better, healthier way forward, Francis seemed to suggest. So yes, as I wrote over a decade ago: How to describe the debut of Pope Francis and not immediately think of grace?

I’m not claiming to be a good Catholic. I’m far from it. I’m a terrible one in many ways. I honestly, sincerely believe the church is wrong in some — but by no means all — of its teachings on sexuality. Lust has undoubtedly mastered me at times the way it has many men, and always will. But I also know my soul has far deeper problems than my love for other men, however muddied with desire; and that the world has lost its way so much more profoundly in other parts of life: in our materialism, our selfishness, our wealth and comfort, our smugness and distraction, and our abuse of our sacred planet.

Francis’ Laudato Si — the great encyclical on climate change — will, in my view, be seen in the future as the work of a true prophet, a damning indictment of our human arrogance and abuse of nature. No previous generation of humans has ever done this much damage to our precious inheritance. And Francis’ moral clarity on this is an enduring legacy, and such a profound rebuke to the predatory, soulless, money-grubbing world of Trump and Xi.

But I loved Francis in the end for nothing more than himself. “We need to remember that all religious teaching ultimately has to be reflected in the teacher’s way of life, which awakens the assent of the heart, by its nearness, love and witness,” he wrote. Francis lived that way. No, of course he wasn’t perfect. He stirred things up a bit, he had a temper, he could be a little too off-the cuff at times, and his campaign against the Latin Mass was unworthily paranoid of him.

But he was not without some reason to be paranoid. The Latin Mass, for example, has been co-opted by reactionaries who are to Catholicism what MAGA is to conservatism. And the ones who dominate the American hierarchy, and have very deep pockets (that whole “eye of a needle” thing is a teaching they conveniently ignore) really did behave contemptibly toward him. And yes, some of them well deserved to be lampooned as ministers of frociaggine or “faggotry”, with their prissy outfits, sense of entitlement, and incensed meta-camp. I wasn’t offended by Francis’ remark. I found it hilarious and all-too accurate about a certain rightwing homo-subculture in the church.

Who knows what follows? Francis himself didn’t pretend to know, because at some deep level, he trusted the Holy Spirit, and he knew the hubris of predicting anything in the messy human world that Godness permeates. Because, as he put it,

God’s word is unpredictable in its power. The Gospel speaks of a seed which, once sown, grows by itself, even as the farmer sleeps. The Church has to accept this unruly freedom of the word, which accomplishes what it wills in ways that surpass our calculations and ways of thinking.

In these days, as I observe more people in the pews, and a growing sense among many that what modernity offers us is empty, that what materialism promises is false, and that what human beings need is something beyond ourselves, I feel the Holy Spirit at work.

Faith needs doctrine, of course. But it also needs doctrinal perspective — and the obsessive focus on relatively minor issues, like communion for faithful but divorced Catholics rather than, say, the far harder commands to love one’s enemy or to renounce all wealth, is more neurosis than religion. In fact, for faith to live in and respond with new language to modernity, it needs the space Francis has created to breathe again, to get away from petty certainties and doctrinal spats, to discern and embrace the unruly freedom of wherever God seems to be leading us.

And the very person of Francis showed to many, far beyond the ranks of Catholics, that in seeking meaning, the weird, strange figure of Jesus of Nazareth still beckons us, is still essential, still there. Francis showed us this meaning, as Jesus did, not by what he said so much as how he lived. Religion, as Oakeshott put it,

is not, as some would persuade us, an interest attached to life, a subsidiary activity; nor is it a power which governs life from the outside with a, no doubt divine, but certainly incomprehensible, sanction for its authority. It is simply life itself.

Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him. May his soul and all the souls of the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

Amen.

(Note to readers: This is an excerpt of The Weekly Dish. If you’re already a paid subscriber, click here to read the full version. This week’s issue also includes: my talk with Frances Lee and Steve Macedo on Covid failures; listener dissent over lab leak with Francis Collins; reader dissent over Trump and immigration laws; 15 notable quotes from the week in news, including three Yglesias Awards for principled stands; 17 pieces on Substack on a variety of topics; a Mental Health Break celebrating early websites; an ornate view from Warsaw; and, of course, the results of the View From Your Window contest — with a new challenge. Subscribe for the full Dish experience!)

A new paid subscriber writes, “We need independent voices that aren’t prone to groupthink.” Another:

Immigrants get the job done. We have led in understanding America since Tocqueville, and the Dish has led in improving America (and my thinking about liberalism) since 2001.

New On The Dishcast: Frances Lee & Steve Macedo

Frances Lee is Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton, and her books include The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized Age. Steve Macedo —an old friend from Harvard — is the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton, and his books include Just Married: Same-Sex Couples, Monogamy, and the Future of Marriage. The book they just co-wrote is called In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us. It’s a must-read right now — accessible, elegantly written and, in the end, a devastating indictment of our politics.

Listen to the episode here. There you can find two clips of our convo — on the demonization of dissent during Covid, and where the right went wrong on the pandemic. That link also takes you to a bunch of commentary on the episode with Francis Collins, when we discussed his early and strong dismissal of the lab leak theory. We also hear from readers on the emergency of Trump 2.0 and the latest transqueer cray-cray.

Browse the Dishcast archive for an episode you might enjoy (the first 102 are free in their entirety — subscribe to get everything else). Coming up: Byron York on Trump 2.0, Claire Lehmann on the woke right, Robert Merry on President McKinley, Sam Tanenhaus on Bill Buckley, Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson on the Biden years, and Paul Elie on his book The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s.

Please send any guest recs, dissents, and other comments to dish@andrewsullivan.com. From a fan of last week’s pod with Francis Collins:

Absolutely incredible conversation. Enlightening and gripping from start to finish. There is no podcast like the Dishcast. Every new episode is one of the highlights of my week.

Dissent Of The Week

A reader responds to last week’s column, “The Bukele Playbook Trump Is Following”:

I agree with every criticism of Trump’s flouting of the law. He must obey the courts, and Kilmar Abrego Garcia must come back to the US. At the same time, there is an asymmetry here. For all of Trump’s illegal over-enforcement of the law, there has been a systematic under-enforcement of the law that preceded it which has not received the same level of judicial urgency.

A lot of people are rightly arguing now for the rule of law, but how do we square that with Sanctuary Cities whose mayors proudly declare they will not enforce the law within their borders? Or consider DACA, which has made ignoring of immigration law an official executive branch policy for the better part of 10 years.

Abrego Garcia’s case has moved through the courts with lightning quickness, while challenges to DACA have been denied or delayed for years. Astonishingly, the Supreme Court even blocked Trump from ending DACA in his first term, arguing that DHS had not provided an adequate explanation of its actions. The Court effectively put the burden on the executive to explain why it should be entitled to enforce the law! And it took until June 2020 to make this ruling, effectively denying Trump the ability to reverse DACA during his entire first term.

At what point does this amount to tacit endorsement of ignoring inconvenient laws? You wrote, “why bother with the hard work of democracy and legislation when you can just seize extra-constitutional powers?” The same could be said of any of this institutionalized under-enforcement.

If under-enforcement is normalized while over-enforcement is an emergency, that is not rule of law; it’s “rule of leniency.” And while I find it disappointing that Vance has appointed himself defender of every Trumpian excess, he’s not wrong to call out this asymmetry. Biden received no legislative or judicial approval to allow millions of people to pour over the border, but now every such case will require judicial approval (and resources) to reverse.

Rule of leniency is exploited by people who want immigration laws to be more lax but don’t have the votes to achieve this legislatively. This was bound to lead to a backlash. Ignoring the courts is not the answer, but it feels like there is a bias in the courts that needs to be corrected.

Read my response here, in the full version of the Dish. As always, please keep the dissents coming: dish@andrewsullivan.com. And you can follow more Dish debate in my Notes feed.

Mental Health Break

Homestar Runner celebrates its 25th — the same age as the Dish. Should we go all the way back to white text on navy blue for our anniversary this summer? Any OG Dishheads out there remember that? Anyway, enjoy:

In The ‘Stacks

This is a feature in the paid version of the Dish spotlighting about 20 of our favorite pieces from other Substackers every week. This week’s selection covers subjects such as the Trump idiocracy, the Trump kleptocracy, and sponsored content for Kamala. A few examples:

A devastating analysis of the online right and Trump from someone … on the online right.

An SF resident living at a dangerous intersection was told by the city it would take three years to install a speed bump — so he took matters into his own hands.

Here’s a list of the substacks we recommend in general — call it a blogroll. If you have any suggestions for “In the ‘Stacks,” especially ones from emerging writers, please let us know: dish@andrewsullivan.com.

The View From Your Window Contest

Where do you think it’s located? Email your guess to contest@andrewsullivan.com. Please put the location — city and/or state first, then country — in the subject line. Proximity counts if no one gets the exact spot. Bonus points for fun facts and stories. The deadline for entries is Wednesday night at midnight (PST). The winner gets the choice of a VFYW book or two annual Dish subscriptions. If you are not a subscriber, please indicate that status in your entry and we will give you a free month sub if we select your entry for the contest results (example here if you’re new to the VFYW). Contest archive is here. Happy sleuthing!

The results for this week’s window are coming in a separate email to paid subscribers later today. From last week’s contest, here’s a sleuth reminiscing about a hitchhiking trip across the Emerald Isle:

Well, I have been to Ireland once before, when I was 19 years old and hitchhiking with my buddy Brad through the UK. My memories vague, I reread my travel journal. It turns out we passed right through this area.

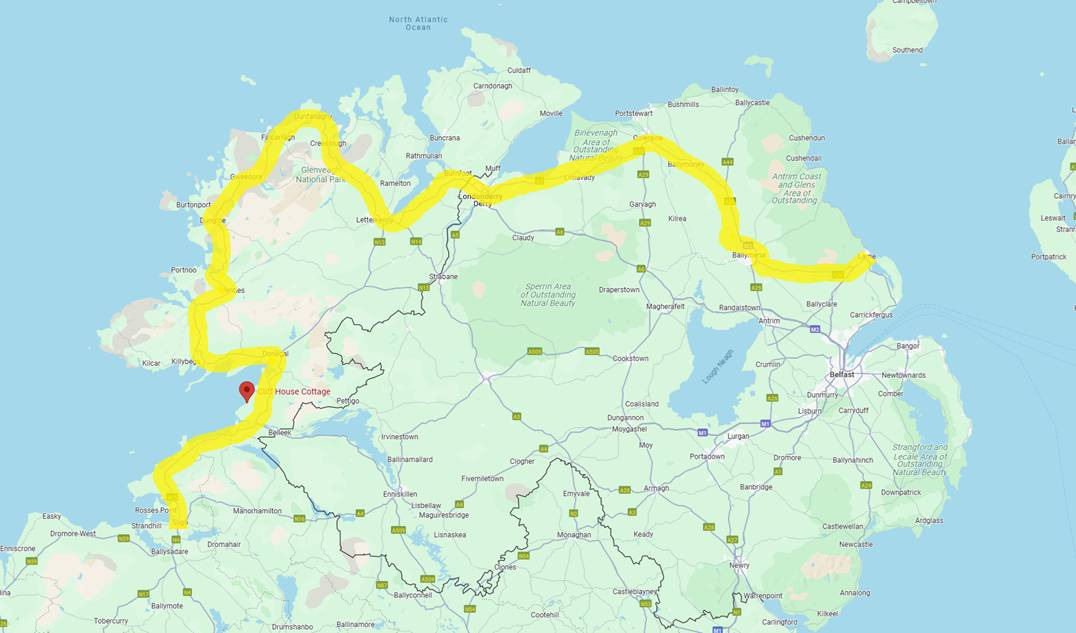

We landed in Larne on a ferry from Stranraer, Scotland. From there, we hitchhiked through Coleraine, Londonderry, Letterkenny, Dungloe, Donegal Town, and on to Sligo. The yellow highlighting below shows our route, and the red pin shows the location of our VFYW this week:

In Letterkenny, we received a ride from an older gentleman named Michael. He invited us to stay at his house and spend the day showing us around his little corner of the world. His wife had died about a year earlier, and I think he enjoyed the companionship of two young men from America.

We stayed up late into the evening, drinking tea in his parlor and talking with Michael and his brother. I wrote in my journal that when the brothers were speaking to each other, we could not understand a word they said, even though they were speaking in English, not Gaelic. Michael remarked that neither could he understand Brad and I when we talked to each other.

Such encounters — very common during our trip — made such a strong impression on the young version of me, and they fostered my faith in humanity and the kindness of strangers. Here’s a photo of Michael, and a snapshot I took of the coastline near his house:

See you next Friday.